Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

Once hunted to near extinction, North Atlantic right whales are now facing new human threats that could end the species. Here are the people risking their lives to save them.

For whale rescuer Mackie Greene, there’s no feeling in the world like seeing fishing ropes slip free of from a trapped whale.

“It’s almost like you could get out of the boat and run home,” he says.

“It’s like you’re bouncing that high – and they must be able to hear us for miles cause you’re hollering and hooting and the whole way in.”

There’s a flipside though: the times when the Campobello Whale Rescue Team head home with little to show for their efforts.

That was the case when they returned to Shippagan, a New Brunswick fishing village, after a long day on the water.

Three entangled North Atlantic right whales had recently been seen in the area and a rescue mission launched. Aerial surveillance had spotted one of the whales about 40 miles (65km) offshore and Greene’s team headed out.

They got close enough to the animal – which can weigh up to 70 tonnes and grow to over 55 feet, about the length of a bowling lane – to see fishing rope wrapped around the tail stock and cutting deep into its flesh.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Weather had kept them off the water for part of the day, and despite the whale’s distress, dusk was falling, and they had to head back to shore.

“You know that whale’s still out there, still suffering,” he says.

After more than a week of work, the team had two small victories – they had managed to partially free two five-year-old males, one almost hogtied by fishing gear keeping it from using its tail when diving.

The time and effort that went into the partial rescue shows just how complex the work can be.

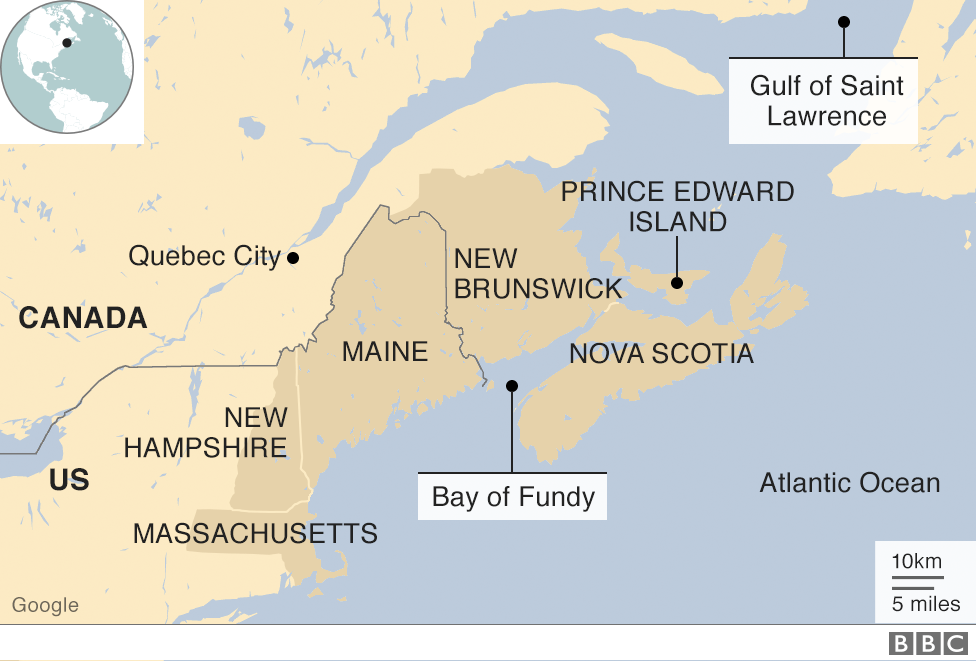

Weather in the Gulf of St Lawrence can be capricious. It’s a huge body of water, and the whales spend a lot of time below the surface, making them difficult to track.

The work is itself dangerous – a “big game of cat and mouse”, says Greene.

“We have to get up pretty close. The danger is the whale changing course, bumping into the boat, knocking the boat over or slapping the boat with the tail.”

Two years ago, Greene’s friend Joe Howlett died after being struck by a right whale’s powerful tail just after he managed to cut it free.

Image copyright

Image copyright

CWRT/IFAW

Whale rescue operations are dangerous and rescuers like Mackie Greene are highly trained

Howlett, a lobster fishermen by trade, had been working disentanglement missions with Greene for over 15 years and was dedicated to helping whales and loved the adrenaline rush that came with a rescue.

“We could work without talking to each other, we knew each other so well,” Greene says.

“We had a pact – if anything ever happened – we knew it was dangerous what we were doing and if anything ever happened we were still going to keep it going, no matter what.”

‘People wouldn’t stand for this’

North Atlantic right whale are like tanks in the water – heavy, wide and dense. They’re also curious, acrobatic animals who can be seen breaching the water and smacking it with their flukes.

For centuries they were lucrative prey for whalers. In the medieval era, they were hunted by the Basques. Later, their blubber helped fuel the Industrial Revolution, when whale oil was used to lubricate factory machinery.

Image copyright

Image copyright

Courtesy Library of Congress

Currier & Ives lithogragh of whalers attacking a right whale

By the early 1890s, commercial whalers had hunted right whales in the Atlantic to near extinction.

Now their habitat overlaps with a heavily industrialised part of the ocean ranging from Florida to Newfoundland. It’s over 1,000 miles of coastline crowded with ship traffic and economically important commercial fisheries.

Most are now being killed by boats and fishing gear.

The blunt trauma of a vessel strike can crush bones and fracture skulls and vertebrae. Propeller wounds can cut deep into flesh.

Researchers documented the case of one female right whale, healed from propeller wounds she received as a calf, who is believed to have died from an infection when she became pregnant 14 years later and her old scars split as she grew.

Entanglements can cause a slow partial amputations or mutilations, and whales who can’t free themselves from the ropes can drag heavy gear for months. They may eventually drown or starve.

“If this were on land, people wouldn’t stand for this,” says Tonya Wimmer a biologist with Marine Animal Response Society (Mars), in Halifax, Canada.

Right whales on the move

For decades, right whales would spend summers in the Bay of Fundy on Canada’s east coast.

The reliable stomping grounds made it easier to bring in conservation measures to make room for the whales.

In 2003, Greene’s colleague, scientist Moira Brown, in collaboration with the shipping industry and the Canadian government, had shipping lanes rerouted around a significant feeding ground and nursery habitat area in the bay – the first time ever international shipping lanes were moved to help a species.

Right whales are increasingly being found in the Gulf of St Lawrence

That small lane shift is credited with reducing the risk of ship strikes there by as much as 90%.

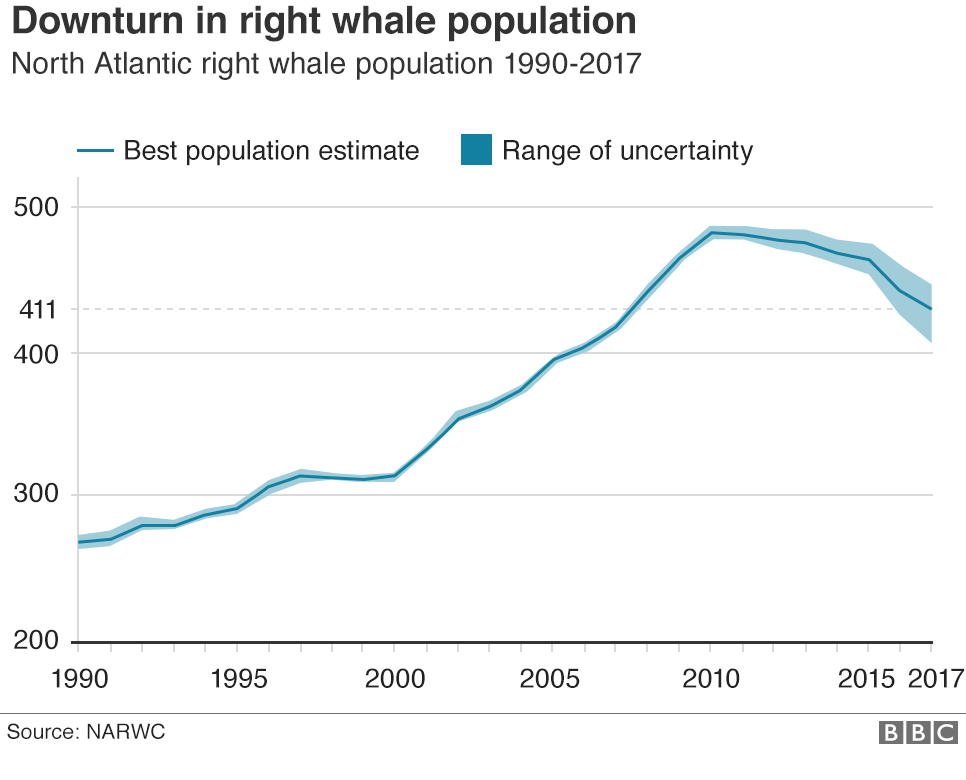

Between 2000 and 2010, the right whale population grew from about 350 to almost 500.

But then the whales began to change their behaviour – and their population began to drop alarmingly.

There are now just over 400 estimated to be in existence.

This June, six right whales were killed, devastating the network of scientists and conservationists fighting to save the animals from extinction. Two more were found dead in July.

It’s unlikely they are the only mortalities, says Cathy Merriman a biologist with Canada’s federal fisheries department.

“For various reasons we know that when we see a dead right whale there’s probably other ones that we don’t see,” she says. “We can probably consider it’s at least double.”

North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium data showing the animal’s estimated population.

One of the dead whales was Punctuation – a whale matriarch researchers had been sighting for almost 40 years.

The species had lost a grandmother, a whale who had given birth to eight calves – and with only about 100 breeding age females right whales still alive – every baby that she could have had in her lifetime.

What we know about her life shows how hard survival is for the species.

Punctuation had been through five separate entanglements and bore the scars from a number of small vessel strikes, including propeller scars on her left flank.

Three of her offspring are confirmed or presumed dead from severe entanglements or ship strikes.

Why is this happening now?

Scientists have known for a few years that some right whales had started spending their summers in waters north of the Bay of Fundy.

In 2015, about 40 right whales were spotted in the Gulf of St Lawrence, and they have been increasingly frequenting the region since.

It’s believed the whales are following copepods—tiny crustaceans that form the base of their diet – as their distribution shifts due to climate change. Right whales have also been having fewer calves, which could be linked to them not getting enough food.

Their habitat shift put them increasingly in the path of ships and fishing gear – but it took a catastrophe to get the Canadian government’s attention.

In 2017, 17 right whales were confirmed killed, 12 of them in Canadian waters. Howlett was also died that summer, bringing global attention to the dangerous work of whale rescue.

“It was like a perfect storm of everything possibly horrible happening all at the same time,” says Wimmer.

“So it was a moment where there was this light bulb that clearly came on for whoever it needed to come on for.”

Image copyright

Image copyright

Boston Globe via Getty Images

Wolverine, a 9-year-old male right whale, lays dead on a beach in New Brunswick in June.

In August of that year, after over nine whale deaths, the government brought in some measures, including large vessel speed restrictions, in parts of the Gulf. It has continued since to slow boats and close some fishing areas to make way for whales.

It is also conducting aerial surveillance to track the whales and to support rescue missions, and is assisting in necropsies.

Organisations like the Campobello Whale Rescue Team and Mars – working on shoe-string budgets and relying heavily on volunteers – have been doing much of the marine response work on the east coast.

They run disentanglement missions for right and other whales, and handle hundreds of calls a year for stranded or dead marine animals.

Now some more federal funding is beginning to flow.

Greene was able to replace the old government surplus boat the Campobello team had been using for rescues since 2002 – a C$300,000 ($230,000;£184,000) upgrade.

“We’ve been asking for this for years, decades, probably, about how we increase this response capacity – for all elements of response – and it’s been tricky, until we had a disaster strike” says Wimmer.

So what more needs to be done?

“It’s not as simple as saying don’t smoke or wear a seatbelt or let’s not put lead in gasoline anymore,” says Sean Brillant, with the Canadian Wildlife Federation.

“We can’t end shipping in the Gulf of St Lawrence. We can’t end fishing in the Gulf of St Lawrence. So where is that middle ground and what works?”

Brillant and others have been working with local fishermen to explore new fishing technology and methods that could curb entanglements.

Image copyright

Image copyright

VW Pics

A North Atlantic right whale breaches the waters in the Bay of Fundy.

Some have hosted researchers experimenting with things like ropeless fishing gear for lobster and crab fisheries on their boats.

That tech, which would secure fishing rope to the bottom of the ocean until it needs to be released, could be hugely beneficial but is years away. It’s still too finicky and expensive to be used widely or reliably.

Other possibilities are “weak” ropes that could break under a certain amount of pressure, making it easier for a whale to free itself, or using underwater microphones to improve whale tracking.

“It’s going to be a combination of things [that will help]. There’s not one single silver bullet,” says Philippe Cormier, whose engineering company, Corbo, is working on a number of projects, including ropeless fishing.

Slowing ships is still the best option to avoid fatal strikes – limited experiments to warn right whales of nearby vessels have been unsuccessful and it may be hard for them to hear approaching ships – but better early detection of whales ahead could help navigators.

Snow crab fishing boats in dry dock in Shippagan, New Brunswick

Brillant says the government has made “difficult and unpopular decisions” in closing down large areas to commercial fishing and slowing shipping traffic – disruptions to important industries.

“We’ve come a long way,” he says. “[But] they can certainly go farther on some decisions.”

Right whales have shown themselves to be a deeply resilient species.

“It always amazes me how tough the whales are, what they can bounce back from,” Greene says. “There’s right whales around with half a tail or missing a flipper. They are really tough. There’s one called Radiator with propeller scars down his back – really chewed up – and he’s still going.”

Despite so many pressures on their population, seven new calves were born this year. It’s not quite a baby boom but enough to give some hope.

Brillant says he believes that the whales and humans can co-exist, “if we can meet them in the middle”.

“At least they’re doing their part to make sure they’re surviving. We need to do our part to make sure we stop destroying them without even meaning to.”

.